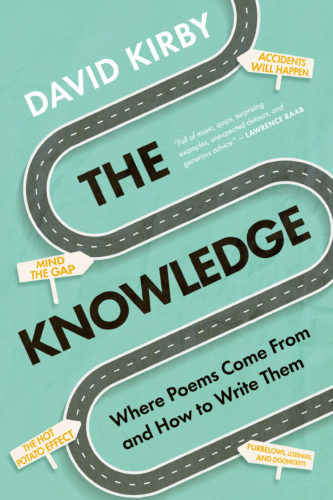

The Knowledge: Where Poems Come From and How to Write Them

A five-time teaching award winner and author of 35 books, David Kirby has written a lively and inviting guide to writing poetry for college students. The Knowledge: Where Poems Come From and How to Write Them, utilizes Kirby’s hospitable, inspirational, and expert voice to help students learn the complex, playful, and meditative art form of poetry. The book’s four sections (“How to Write a Poem,” “How to Write a Really Good Poem,” “Immortality is Within Your Grasp,” and “You Graphomaniac, You”) are staggered to gradually build student confidence and skill, and include works from over 70 poets—including Joy Harjo, Terrance Hayes, Marilyn Nelson, Franny Choi, Emily Dickinson, and Natalie Diaz—to illuminate key points and spur student reflection and writing. The Knowledge, writes Kirby, helps students craft poems the way Jimi Hendrix talked about making music—“Learn everything, forget it, and play.” Each chapter is brimming with tips and suggestions for writing great poems and concludes with summative talking points and dozens of unique prompts to nudge students to contribute to an art form that is “thrumming with life.”

The Knowledge: Where Poems Come From and How to Write Them

A five-time teaching award winner and author of 35 books, David Kirby has written a lively and inviting guide to writing poetry for college students. The Knowledge: Where Poems Come From and How to Write Them, utilizes Kirby’s hospitable, inspirational, and expert voice to help students learn the complex, playful, and meditative art form of poetry. The book’s four sections (“How to Write a Poem,” “How to Write a Really Good Poem,” “Immortality is Within Your Grasp,” and “You Graphomaniac, You”) are staggered to gradually build student confidence and skill, and include works from over 70 poets—including Joy Harjo, Terrance Hayes, Marilyn Nelson, Franny Choi, Emily Dickinson, and Natalie Diaz—to illuminate key points and spur student reflection and writing. The Knowledge, writes Kirby, helps students craft poems the way Jimi Hendrix talked about making music—“Learn everything, forget it, and play.” Each chapter is brimming with tips and suggestions for writing great poems and concludes with summative talking points and dozens of unique prompts to nudge students to contribute to an art form that is “thrumming with life.”

Sample Now

The Knowledge: Where Poems Come From and How to Write Them is available to sample now on Bookshelf, VitalSource’s digital platform.

Available for Winter/Spring 2023 Adoption

ISBN: 978-1-7355940-3-3 – VitalSource – Digital-Only – $29

ISBN: 978-1-7355940-2-6 – Print — Paperback – $44.95

Campus bookstores can place digital-only purchase orders directly via VitalSource’s catalog. For print-only and bundle orders, please contact our Order Fulfillment team directly (orders@fliplearning.com).

Request Complimentary Copy

Features

The Knowledge will be available on VitalSource’s digital, interactive textbook platform, Bookshelf, which includes the following features:

- Annually updated links to relevant online sources;

- Helpful instructor supplemental materials;

- Easy access from any browser and compatible with all major devices, including desktop computers, laptops, tablets, and smartphones.

Table of Contents

Since we do not spend all day in a single cortex or a single hemisphere of the neocortex but flip back and forth constantly from one to the other, the secret is to be aware of the flips, to bring the deep ancestral images of the reptile brain and the fiery passions of the early mammalian brain up into the well-lit chambers of the new brain. There they can be tested both logically (in the left hemisphere) and intuitively (in the right), examined, sequenced, revised, sent back to their places of origin, if necessary, and retrieved so that the entire process can start all over again.

The result is a poem.

You can also sum up the creative process this way: art is the deliberate transformed by the accidental. That is, you start deliberately, in your studio or office with your paints or pens or whatever it is you use as well as a cup of tea or coffee to get you going. Then you put some colors on the canvas or some words on the page. You might work that way the whole morning in a calm and steady way, but sooner or later, something will happen—you’ll hear a sound outside or get a phone call or remember something that you’d read the day before—and what you’re doing will change.

. . . if it works, a poem is more likely to be half understood rather than fully comprehended. After all, unless Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell are all wet, a poem tends to have one foot in the unconscious and one in the sunshine, one foot in the base camp and one foot already heading up the mountain.

Here’s my own metaphor: in the time necessary to get from the start of poem to its conclusion, the poet is operating like a pilot in the early days of aviation, relying less on external controls, even in the case of highly formal poetry, and more on his own experience and intuition to gauge the plane’s position and performance as he tries to find his way and then bring the craft in for a nice soft landing.

The German critic Wolfgang Iser has described how gaps work in The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response (1976). Iser argues that texts contain gaps or blanks that powerfully affect the reader, who must explain them, connect what they separate, and create in his or her mind aspects of a work that aren’t in the text but are motivated by the text.

A more homey way to put it is to say that Nelson is offering the reader a very effective version of the ring-toss experiment that I talk about in Chapter 2. People seldom say everything they think or mean when they are interacting with others. Here we are given the basics—really, the least important elements of the interaction. The crucial elements are the ones we come up with ourselves.

The good news is that you don’t have to be Neil Young or Michelangelo to do the kind of work I’m talking about here. And while it might seem as though I’m saying you need to create something magnificent and then rough it up in some way, the most effective way to write a poem with a gap in it is to simply put two unrelated subjects next to each other and leave space for them to interact. Let them work it out! This will take some trial and error, but what have you ever done that you’re proud of that didn’t involve trial and error? Once you get the right two subjects, they’ll figure out how to talk to each other. All you need to do is listen and write down their conversation.

Poetry always helps. I got that from a friend whose adult daughter was grieving the death of a beloved pet, and the friend said her daughter replied, “Poetry always helps.” I think that’s true . . . Think about the last time you wrestled with a swimsuit or a pair of pajama bottoms or some other article of clothing that has a drawstring and you had to grapple with a knot, teasing it out with your nails until the hard center dissolved and you could separate it into two strands. No poem by someone else speaks directly to your moment, but when your mind’s in a knot, a well-turned piece of writing can untangle that knot, and then you can retie the strings in a new way or just let them dangle, if you like. The materials that made the knot haven’t changed, but you can deal with them now.

. . . let me illustrate what full dimensionality is by stepping away from poetry for a moment.

Think instead of pop music: why did Sinatra have the impact that other singers didn’t, and why did the Beatles spur Beatlemania—why is there no Gerry and the Pacemakers-mania? It’s because the Beatles’ work was fully dimensional. Those songs contain every emotion we’ve ever felt, and they hint at mysteries we can’t articulate; in other words, you get the whole roller coaster ride.

Say you’re on an iron roof, fleeing a lion, but you’re dressed like a ballerina except that you’re wearing magnetic shoes. Now there are iron roofs in the world and lions and ballerinas and shoes and magnets, and you yourself are in the world as well. But these six ingredients have never come together anywhere except in your dream, and it’s this overdetermination that makes your dream something that frightens and delights you and that you tell others about the next day.

So how do you overdetermine rather than merely determine a poem?

Almost nothing in American culture tells us to get bigger. Every explicit weight-loss ad, every photo of a model or starlet implicitly tells us to put down that fork, drop that doughnut, get skinny. Not Terrance Hayes, though. He’s the one exception among the millions of spokespersons out there telling us that there’s something wrong with us if we are not seriously underweight. He says it’s okay to be a big guy, only that’s not what he’s saying. No, Hayes is telling us to be big in spirit—as the last line says (not once but three times), big in heart. Anybody can embrace a cliché. Turn the cliché on its head, though, and you’re looking at a profound truth.

Prose poems are notoriously hard to pull off, because they relinquish the control that only line and stanza can provide. So if you’re going to write a prose poem, it better land. This one does. Note that the trick here is the same one that Molly Fisk uses. It’s easy: you introduce the negative content, then you step away from it. Dougherty can whine or attack the editor (people do, believe me), but instead he shrugs it off. This is a poem that endorses perspective: yeah, my poem got turned down, but I still have basketball and the moon and someone who loves me.

There is lot in the first part of The Knowledge about the value of accidents, but that’s because accidents often shape our lives more than our deliberate actions do. What we learn about accidents in music can teach us much about poetry.

Yes, stories can make sense. But aren’t the best ones or the ones we like most (and what’s the difference) the ones we treasure precisely because they don’t always make sense? One of the people who can teach us the most about narrative is the English critic Frank Kermode, who says stories do two things at once: they proceed in a way that allows to make sense of the world while, at the same time, they charm us with details that are indifferent, even hostile, to story.

So Márquez praises the direct speech of country folk, and Emerson does the same with blue-collar workers. Directness—simplicity—is just the start, though. If fine writing were just a matter of showering one’s readers with bullets, then best-sellerdom would be every blacksmith’s side hustle.

The voice we hear is one that will keep talking to us whether we want it to or not.

If you compare “Hip Hop Analogies” to Yolanda Franklin’s earlier “Elegy for Shawn: Omega B-Boy Stance,” you can see why I put so much influence on the similarities between poetry and music. But notice the differences: whereas Franklin’s poem lifts off and circles and returns like improvisational jazz, “Hip Hop Analogies” is as tight as one of Mozart’s fugues, in which one phrase (“If you be”) is introduced and then interwoven with another (“then I be”). What a lovely idea: Betts is just speaking the truth that you can be one thing and I can be another, yet we become something so much bigger and better when we come together as one.

The first thing you need to know is that a formal constraint doesn’t impose a limit of any kind. To the contrary, a formalism can push you toward newness and keep you from being lazy and doing something you’ve done a dozen times before.

The great choreographer George Balanchine said it’s necessary to outline the steps a dancer must take because dancing is tiring, and if you just rely in instinct, you might just take a timid step forward when it’s time to make a beautiful leap.

I want you to cultivate your sense of this world’s richness in a way we haven’t talked about in depth yet. You have so much at your disposal: your memories, your present life, the ideas and images that come to you out of nowhere, and now the great words of the past, the ones that Keats said were written by “the mighty dead.” How will you use them?

You create vision by not creating it. Octavio Paz described his poetry as “the apple of fire on the tree of syntax.” That’s what you give the reader, your imagery and your syntax. Those are to the reader what a compass and a walking stick and a hat to keep the sun off and a canteen are to the traveler. You give the reader the necessary tools, and you point them down the path, and you let the reader create the vision.

Remember, too, that we’re all on one spectrum or another and while there are people who are compelled to write too much, there are many of us who have to write, not all the time, but regularly.

That’s me, and I’m thinking that it might be you, too. If so, we’re not graphomaniacs, but we do have graphomaniacal tendencies. Having a particular disorder can be terrible, but having its tendencies is not bad at all and, in fact, can be quite productive.

The second surprise is that the four tricks of the trade I’ve described as essential to any good poem are also indispensable to any piece of good writing. For example, a good novel has a good hook: What would Moby-Dick be without “Call me Ishmael”? Each hit song has an unmistakable voice: you could play “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” loud and fast, but the version most people remember is the wistful one that Judy Garland sang. Every good play is saturated with details: if Macbeth didn’t have all those witches and sword-fights in it, it would just be a dull treatise on Scottish politics. And each of these has its own Big Idea: pride, nostalgia, ambition.

What’s really exciting to me is watching a young poet write one poem and then another and then ten and thirty and forty until he or she develops an artistic signature, a look on the page as distinctive as someone’s handwritten name at the bottom of a page. What’s equally exciting is to watch that signature change. As with Thomas Kuhn’s scientific paradigms, the best writers become the self they were meant to be, and then they became someone else. Indeed, they should.

There is in the exchange between artist and audience a shock of recognition as because the audience looks at the artist and sees what it can be, just as the artist looks out at the throng of ecstatic faces and thinks, “As you are, so I was—who am I now?” In the exchange that takes place between artist and audience, both agree, not to answer these questions, but to ask them.

It’s this exchange between speaker and listener, between writer and reader, between singer and audience that is at the heart of any art.

Some writers look at the objects of this world and put a coat of paint on them so that they appear a little different, and that passes as art. But Shakespeare never gives you a new version of what already exists. He doesn’t depict reality. He creates reality. It’s the difference between someone going to a store and buying you a piece of furniture or disappearing into their workshop for weeks and making one for you that’s more beautiful than anything the store could offer. Which gift pleases you more?

Emerson’s sense of prayer as mindful action appeals to my students here at Florida State, especially as graduation nears and the world of work beckons. In this job market, you can say of poetry classrooms what is said often of foxholes: there are no atheists there. My students are prayerful, though in the Emersonian way, which is to say they pray by doing, because they know that before they find their place in the world, they have a journey ahead of them.

The seamless life: I can’t say I live it every day. But I’m trying.

Isak Dinesen said, “I write a little every day, without hope and without despair.”

Henry James said, “We work in the dark—we do what we can—we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion, and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.”

E. L. Doctorow says, writing is “like driving a car at night: you never see further than your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

In other words, b + T = P.